Dynamic Recompilation Part 2

Who ya gonna call?

Introduction

In this part we’re going to invest some significant time in calling functions from our dynamically generated code. We’re going to need this because until we can replace an interpreter function with its recompiled version we can get away with calling the old interpreter function. In fact, for the more complicated MIPS instructions, we may never provide a recompiled version.

Along the way we’re going to discuss in a bit of detail the x86–64 instruction set and how it is encoded. Nothing terribly in depth but hopefully something that will serve as a reference for what follows.

We’ll also learn a bit about stack alignment and what happens when you get it wrong.

I’m going to be using the Intel syntax throughout, but my IDE (JetBrains’ CLion) has a preference for the AT&T syntax1.

Keep in mind therefore that when inspecting the disassembly the arguments are reversed!

Recap

Last time we got as far as declaring a simple class to encapsulate an executable region of mapped memory and writing a single x86–64 Return instruction to that buffer.

CodeBuffer buffer(1024);

buffer.Byte(0xC3u);

buffer.Protect();

buffer.Call();

This, while a significant step forward, does absolutely nothing.

Further abstractions

Having to remember that 0xC3 means Return and having multiple 0xC3s littered across the code is not going to help with the readability or with the cognitive overhead. Many, if not the majority, of the x86–64 instructions span multiple bytes and having multiple calls to Byte method is going to make things unreadable pretty quickly.

Let’s introduce at this point another layer of abstraction called the Emitter.

class EmitterX64 {

public:

explicit EmitterX64(CodeBuffer&);

void Ret();

private:

CodeBuffer& buffer;

};

The implementation of the Ret function is pretty straightforward.

void EmitterX64::Ret() {

// RET

buffer.Byte(0xC3u);

}

This isn’t a perfect level of abstraction. The x86–64 instruction set is large and there are many instructions doing similar things with different types of arguments and so on. It is probable that we’ll end up with multiple methods with similar names and at some point it will become difficult to know which is which.

Call-Me Risley

The next task is to finally call a function. We’d like to achieve something like

void HelloWorld() {

std::cout << "hello world" << std::endl;

}

CodeBuffer buffer(1024);

EmitterX64 emitter(buffer);

emitter.Call(???HelloWorld???);

emitter.Ret();

buffer.Protect();

buffer.Call();

As far as I understand it the x86–64 offers two practical forms of the Call instruction: CALL rel32 and CALL r/m64234.

You can use the first form when you know in advance the relative location of the Host Program Counter in relation to the call target. That is to say, in position dependent code.

You have to use the second form, known as the register-indirect form, when you don’t know in advance the relative location of the Host Program Counter in relation to the call target. That is to say, in position independent code. This form without special handling however is an attack surface for the SPECTRE vulnerability5.

As things are already quite complicated we’ll go with the relative form.

Firstly, we need to know the address of the target function. To that end we have the helper function

template<typename T>

uintptr_t AddressOf(T& target) {

return reinterpret_cast<uintptr_t>(std::addressof(target));

}

and similarly the addition to the CodeBuffer class of

uintptr_t CodeBuffer::Position() const {

return reinterpret_cast<uintptr_t>(reinterpret_cast<uint8_t*>(buffer) + pos);

}

With these two functions we can get the address of

- The target function, and

- The Host Program Counter prior to the call.

We can now add the CallRel32³ method to the EmitterX64 class

void EmitterX64::CallRel32(uint32_t rel32) {

// CALL rel32

buffer.Byte(0xE8u);

buffer.DWord(rel32);

}

and also a convenience method

void EmitterX64::Call(uintptr_t target) {

CallRel32(target - (buffer.Position() + 5u));

}

The mystery 5 here is because the call is made relative to start position of the next instruction following the Call. A CALL rel32 instruction occupies 5 bytes, and we need to take this into account when calculating the relative offset.

Our desired code snippet now becomes

void HelloWorld() {

std::cout << "hello world" << std::endl;

}

CodeBuffer buffer(1024);

EmitterX64 emitter(buffer);

emitter.Call(AddressOf(HelloWorld));

emitter.Ret();

buffer.Protect();

buffer.Call();

Footnote

To me this feels clunky and awkward. There are perhaps easier ways to compute the address of a function in C++ without resulting to templating and relative jumps are restricted to ± 2 GiB limit. However, this appears to suffice for now so until it becomes a problem we will let sleeping dogs lie.

Stack Alignment Woes

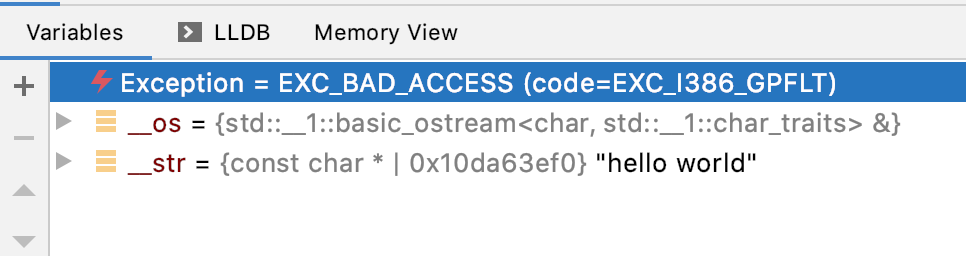

Let’s give this a go and see what happens. Stepping through we arrive happily in the HelloWorld function but when we try to call another function to print out our greeting it all goes wrong.

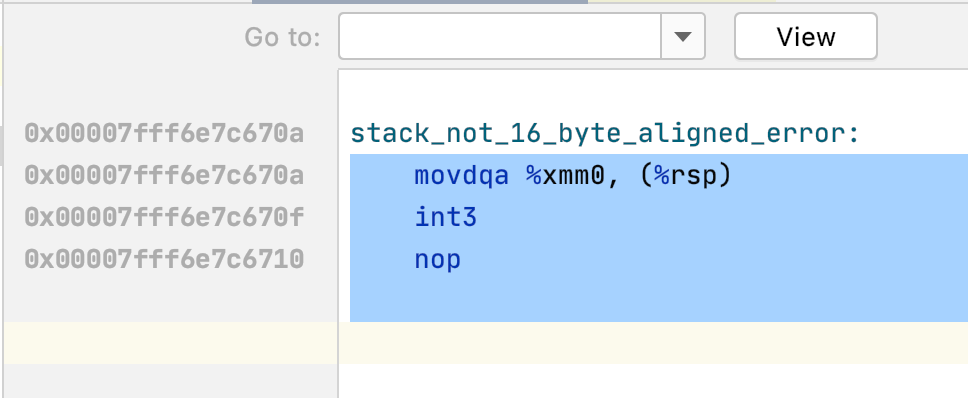

It looks like we did something very, very bad. But this doesn’t tell us very much. Thankfully my IDE’s disassembly view gives us a much better hint.

It appears as if we have violated the System V AMD64 ABI requirement that the stack must be aligned on a 16-byte boundary. Interestingly, it looks like the code in question is trying to put an SSE register on the stack.

The Intel x86–64 family of processors store the stack pointer in the RSP register. But the question is how did our stack become not aligned?

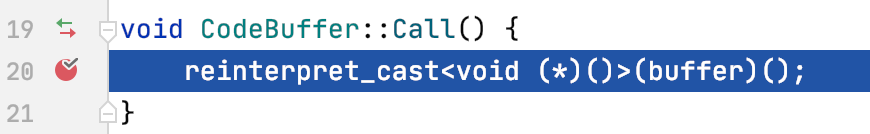

First we need to go back and look at what’s happening during the CodeBuffer::Call method

The disassembly at this point looks like.

(lldb) disassemble

tutorial`rbrown::CodeBuffer::Call:

0x10bf51700 <+0>: pushq %rbp

0x10bf51701 <+1>: movq %rsp, %rbp

0x10bf51704 <+4>: subq $0x10, %rsp

0x10bf51708 <+8>: movq %rdi, -0x8(%rbp)

0x10bf5170c <+12>: movq -0x8(%rbp), %rdi

-> 0x10bf51710 <+16>: callq *(%rdi)

0x10bf51712 <+18>: addq $0x10, %rsp

0x10bf51716 <+22>: popq %rbp

0x10bf51717 <+23>: retq

(lldb) register read rbp rsp

rbp = 0x00007ffee3cb1a60

rsp = 0x00007ffee3cb1a50

We’re about to make a Call which is expected and the RSP register is 16-byte aligned. So far, so good. The RBP register is also of interest here as is often used in conjunction with RSP. Stepping into the code we generated gives:

(lldb) thread step-inst

(lldb) disassemble

-> 0x10bf6c000: callq 0x10bf4f7c0 ; HelloWorld

0x10bf6c005: retq

(lldb) register read rbp rsp

rbp = 0x00007ffee3cb1a60

rsp = 0x00007ffee3cb1a48

On the plus side the Call is targeting our HelloWorld function but the RSP is no longer aligned on a 16-byte boundary because the previous Call pushed the 8-byte return Program Counter onto the stack.

Finally, let’s look at what’s happening under the hood prior to attempting to send “Hello World” to the console:

(lldb) disassemble

tutorial`(anonymous namespace)::HelloWorld:

0x10bf4f7c0 <+0>: pushq %rbp

0x10bf4f7c1 <+1>: movq %rsp, %rbp

0x10bf4f7c4 <+4>: subq $0x10, %rsp

0x10bf4f7c8 <+8>: movq 0x2831(%rip), %rdi ; std::__1::cout

0x10bf4f7cf <+15>: leaq 0x271a(%rip), %rsi ; "hello world"

-> 0x10bf4f7d6 <+22>: callq 0x10bf51d0e ; operator <<

0x10bf4f7db <+27>: movq %rax, %rdi

(lldb) register read rbp rsp

rbp = 0x00007ffee3cb1a38

rsp = 0x00007ffee3cb1a28

Again, RSP is not 16-byte aligned and on this occasion this proves fatal. Therefore, we must make sure that RSP is 16-byte aligned before issuing the call. How do we do this?

One approach would be by subtracting 8 from RSP prior to issuing our call to HelloWorld. As with all stack operations however this operation must have its reverse applied before returning from our function back to the host C++ program, and so we must also add 8 to the RSP on exit. Like so,

CodeBuffer buffer(1024);

EmitterX64 emitter(buffer);

??? SUB RSP, 8 ???

emitter.Call(AddressOf(HelloWorld));

??? ADD RSP, 8 ???

emitter.Ret();

buffer.Protect();

buffer.Call();

We’ll discuss how to do this in the next section as we’ll first want to delve a little into how the x86–64 processors encode their instructions.

Note: This isn’t really the normal way to handle stack alignment, and it would be better in future to follow convention.

Of REX and ModR/M

Asking an x86–64 assembler to turn SUB RSP, 8 into a sequence of bytes will produce the following

SUB RSP,8 ; 48 83 EC 08

We can also ask the assembler to do the same for ADD RSP, 8

ADD RSP,8 ; 48 83 C4 08

If we look at the two 4-byte sequences the only difference is the third byte. What is going on here?

- The first byte (48) is the REX.W prefix. Very roughly speaking this is when we want to tell the processor we want to perform a 64-bit operation. There’s a little more to it but for now this explanation will do.

- The second byte (83) is the Operation Code or opcode for short. But since the Operation Code is the same in both cases how does the processor tell the difference between Add and Subtract?

- The third byte (EC/C4) is the ModR/M byte. This byte is used to encode register numbers or information about other forms of addressing.

- The final byte (08) is the immediate value we wish to add or subtract to the register.

Putting things together

Consulting the Intel references we have that

REX.W + 83 /0 ib | ADD r/m64, imm8

REX.W + 83 /5 ib | SUB r/m64, imm8

There’s REX.W, the Operation Code we expect, for some reason either /0 or /5 in the ModR/M position followed by an immediate byte (ib).

Let’s start by defining the bits used in the ModR/M byte.

| 7 6 | 5 4 3 | 2 1 0 |

|---|---|---|

| mod | reg | rm |

When both the mod bits are set, and indeed they are in the current case, then we can usually assume that reg and rm refer to registers.

Operation Code 83 means that we want to perform an operation on a register with an immediate 8-bit operand. Since there is only one register involved (RSP, encoded as 4 in the rm field) the reg field is used to encode the operation. Add is denoted by 0 and Subtract is denoted by 5. The encoding of the values we have (3, 0, 4) and (3, 5, 4) into bytes is left as an exercise to the reader.

Some of you might have noticed that the x86–64 processor has 16 registers, and we need 4 bits to encode the entire set of registers but the ModR/M byte only affords 3 bits per register. The workaround for this is the REX prefix byte.

The REX prefix is defined as

| 7 6 5 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 1 0 0 | w | r | x | b |

When w is set we indicate to the processor we wish to perform a 64-bit operation (as opposed to a 32-bit one). Hence, in this instance the REX.W prefix.

The r field is used to extend the ModR/M.reg field.

The b field is used to extend the ModR/M.rm field.

The x and b fields also have uses in something called SIB (Scale-Index-Base) byte but this out of scope for this discussion.

Now that we have all this knowledge we can define two helper methods

uint8_t Rex(uint32_t w, uint32_t r, uint32_t x, uint32_t b) {

return 0x40u + ((w & 1u) << 3u) + ((r & 1u) << 2u) +

((x & 1u) << 1u) + (b & 1u);

}

uint8_t ModRM(uint32_t mod, uint32_t reg, uint32_t rm) {

return ((mod & 0x3u) << 6u) + ((reg & 0x7u) << 3u) +

(rm & 0x7u);

}

and we extend our emitter with

void EmitterX64::AddR64Imm8(uint32_t rm, uint8_t imm8) {

// ADD rm, imm8

const uint8_t rex = Rex(1, 0, 0, rm >> 3u);

const uint8_t mod = ModRM(3, 0, rm);

buffer.Bytes({ rex, 0x83u, mod, imm8 });

}

void EmitterX64::SubR64Imm8(uint32_t rm, uint8_t imm8) {

// SUB rm, imm8

const uint8_t rex = Rex(1, 0, 0, rm >> 3u);

const uint8_t mod = ModRM(3, 5, rm);

buffer.Bytes({ rex, 0x83u, mod, imm8 });

}

Please note the Intel convention with the method naming. They’re intended to read like ADD R64, Imm8 meaning add to a 64-bit register an Immediate 8-Bit quantity.

Coming up for air

This has been quite a journey so let’s bring it all together with the final code sample

void HelloWorld() {

std::cout << "hello world" << std::endl;

}

CodeBuffer buffer(1024);

EmitterX64 emitter(buffer);

emitter.SubR64Imm8(RSP, 8);

emitter.Call(AddressOf(HelloWorld));

emitter.AddR64Imm8(RSP, 8);

emitter.Ret();

buffer.Protect();

buffer.Call();

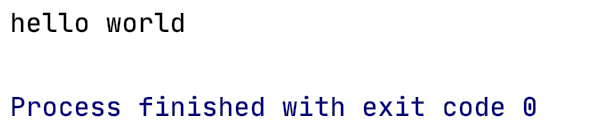

and present the final output

Conclusion

In this article we discussed how we might call a C or C++ function from within out dynamically recompiled code.

We also explored the conventions we must observe when calling that function, namely 16-byte stack alignment.

Finally, we examined in some detail how the x86–64 processor instruction set encoding with a focus on the REX prefix and ModR/M byte.

Next time we’ll discuss stack frames and how the approach taken to stack alignment here isn’t necessarily the best and what the alternatives are.