Dynamic Recompilation Part 8

You are invited to spend an hilarious weekend in the English countryside

Introduction

In this, the last and final part of the series, we’re going to talk about branch instructions. Branch instructions are needed for things like loops and function calls.

We’re going to discuss the role branch instructions play in a recompiler and what that means for our implementation.

Before implementing branch instructions in either the interpreter or the recompiler we’re going to discuss another MIPS feature called the branch delay-slot.

We’re also going to examine the role exceptions play in branch delay-slots.

In the conclusion we’re going to wrap up the series and talk about the things that would need to be changed in order to make the recompiler actually useful.

Recap

In the last part we discussed other hypothetical ways a MIPS recompiler might handle load delay-slots. This included the idea of possibly reordering instructions and talking briefly about Single static-assignment form and how this could help.

There were no code changes, and so we’ll continue in this part to adapt our existing recompiler to handle branches.

We’ve gone on holiday by mistake

Let’s take a look at what branches are and how they are used with reference to C++.

Branch instructions are the special magic sauce that make things like loops and function calls possible.

If you’re looking at the following C++ loop

int i = 12;

int j = 9;

while (i > 0) {

j += 1;

i -= 1;

}

then, assuming our compiler doesn’t do any optimisation, there’s a fair chance the underlying MIPS assembly may look something like

LWI R4, 12 ; load 12 into R4 (i)

LWI R5, 9 ; load 9 into R5 (j)

loop:

ADDI R5, 1 ; add 1 to R5 (j)

SUBI R4, 1 ; subtract 1 from R4 (i)

BGTZ R4, loop ; if R4 greater than zero then go back to loop (ADDI R5, 1)

NOP

The last instruction, BGTZ (branch greater than zero), will make the processor jump back the ADDI instruction if the contents of R4 are greater than zero, otherwise the processor continues to the NOP instruction. It does this by manipulating the processor’s Program Counter.

BGTZ is an example of a conditional branch instruction.

A C++ function call

void MyFunc1() {

...

MyFunc2();

...

}

void MyFunc2() {

...

}

may, in MIPS assembly, look something like this

my_func_1:

...

J my_func_2

NOP

...

my_func_2:

...

After executing the J (Jump) instruction the processor’s Program Counter is changed to the address of the instruction at the my_func_2 label.

This is an example of an unconditional branch as the processor doesn’t evaluate any arithmetic comparison before changing the Program Counter.

Now that we have an overview of what branches are let’s discuss what they mean for a dynamic recompiler.

Listen, we’re bona fide, we’re not from London

All the way back in Part 1 we mentioned that the way Dynamic Recompilers often work is to recompile the guest code until they encounter a branch instruction. Why is that?

To answer that question let’s examine an approximation of a Dynamic Recompiler’s main loop

while (true) {

const uint32_t pc = processor.GetPC();

void* code = codeCache.Get(pc);

if (!code) {

code = codeCache.Put(pc, RecompileCode(processor, pc));

}

// reinterpret code as a function pointer and call

reinterpret_cast<void (*)()>(code)();

}

What the loop is doing is first making a note of the Guest Processor’s Program Counter. It’s then querying something called a Code Cache for recompiled code it may have at that address. If there is no code found then it recompiles the Guest Code at the Program Counter and puts it in the cache. Finally, it calls the recompiled function and, crucially, it expects it to return. When it returns the recompiled code is expected to have updated the Guest Processor’s Program Counter so that the cache can be queried again.

Note: It’s worth mentioning at this point that sometimes Recompilers check for external interrupts here. Real processors check for interrupts after every instruction, but it’s usually sufficient, at least for simulating MIPS and later processors, to check for them less often.

Branch instructions are therefore important because they can change the Guest Program Counter in a non-sequential manner. This is why once recompilers encounter a branch instruction they stop recompiling and emit code to return control back to the main program.

As always, however, this statement about stopping whenever a branch instruction is encountered isn’t strictly true. Let’s consider the first example in the previous section as to why

my_prog:

LWI R4, 12 ; load 12 into R4 (i)

LWI R5, 9 ; load 9 into R5 (j)

loop:

ADDI R5, 1 ; add 1 to R5 (j)

SUBI R4, 1 ; subtract 1 from R4 (i)

BGTZ R4, loop ; if R4 greater than zero then go back to loop (ADDI R5, 1)

NOP

Let’s assume that the Guest Program Counter is at my_prog and the Code Cache is empty.

When the main loop queries the Code Cache at my_prog no code is found since the cache is empty.

The recompiler will then start recompiling the code at my_prog and continue until it has recompiled BGTZ.

This code will then get executed and when this code returns the Guest Program Counter will be at loop.

The main loop will now query the Code Cache and find no code at loop. The main loop will then recompile

everything between loop and BGTZ and execute it.

The problem with this is that we’ve effectively recompiled the same block of code twice. This means that

- we do almost twice the amount of work we need to and

- we use almost twice as much space as we needed to.

A better approach here would be to implement some kind of loop detection and only recompile the code once. (When a branch is found to be part of loop then rather than stopping the recompilation there and then, the recompiler continues).

The second example is also not without its problems. If for example, MyFunc2 is very small,

void MyFunc1() {

...

MyFunc2();

...

}

void MyFunc2() {

x += 1;

}

then in some cases it might make sense to have the recompiler follow the branch and effectively inline the function in the recompiled code. The above would then become

void MyFunc1() {

...

x += 1;

...

}

Deciding when to do this should probably be left to some heuristic. If you do it too often, you might end up

recompiling MyFunc2 multiple times, which might not be what we want. On the other hand, if you don’t do

it all you might not be able to optimise small functions.

Don’t threaten me with a dead fish!

Having talked about branches and recompilers in general, it’s now time to turn our attention to another fun aspect of the early MIPS architecture, the branch delay-slot!

Branches, like loads, on MIPS processors don’t take effect immediately and take an extra instruction to complete. Instructions immediately following a branch are said to be in the branch delay-slot, and they are always executed.

BGTZ R4, loop ; branch

ADD R5, R1, R2 ; branch delay-slot, R5 is updated then branch taken

Branch delay-slots are a consequence of the early MIPS instruction pipeline design. For purposes of argument, let’s assume there are three stages (the reality is that there were five, but three should be sufficient to illustrate the problem). The first stage would contain the instruction just fetched from memory, the second stage would contain the instruction that’s been decoded and about to be executed and the third stage would contain the instruction that’s currently being executed.

In the situation above the BGTZ instruction is in the 3rd stage and the ADD instruction is in the second. By the time the processor has completely executed the BGTZ instruction, the ADD instruction is already being moved into the third stage. In the early MIPS pipeline it’s therefore impossible to stop the ADD instruction from being executed1.

This could have been avoided by doing something like flushing the pipeline, but then the processor would have to waste two instruction cycles refilling the pipeline before it could resume doing useful work again, effectively stalling the processor. The MIPS designers decided it would be better not stall the CPU completely and elected instead to only have a single instruction delay. Besides, they thought, you could put an instruction that did useful work in the branch delay-slot.

This is same design philosophy that influenced the load delay-slot but the reality, in most cases, turned out to be

BGTZ R4, loop ; branch

NOP ; do nothing

A later revision of the MIPS architecture (R4000) introduced the Branch Likely class of instructions that allowed you to prevent the instruction in the branch delay-slot from being executed and an even later revision removed them again because they caused problems with parallelism2.

I have of late — but wherefore I know not — lost all my mirth…

Although it was common practice putting NOP into branch delay-slots our recompiler is going to have to handle cases when the compiler or programmer elected to put a meaningful instruction into a branch delay-slot.

Where things get interesting is when the compiler decided to put an instruction that can cause an exception in the branch delay-slot.

Consider as an example

loop:

...

BGTZ R4, loop ; branch

LW R2, (R3) ; load R2 with contents of (R3)

ADD R5, R8, R9 ;

and let’s assume that during the execution of the LW instruction an exception occurs.

Normally, the processor would notify Coprocessor 0 that an exception has happened and tell it that the exception happened at the address of the LW instruction. The coprocessor will then instruct the processor to invoke an exception handling routine, and upon returning from the handling routine the processor will try to execute the LW instruction again.

Usually the processor would then proceed to the ADD instruction. But this isn’t what we want. Had the LW instruction completed normally in the first place the processor would have branched back to loop. But as it stands the processor can’t differentiate between the two circumstances and the processor is now executing the wrong instructions.

How was this solved? Well the MIPS designers observed that re-executing the branch instruction is harmless in all cases (branch instructions themselves can’t raise exceptions). So they decided that when an exception occurs in a branch delay-slot the address of the branch is passed to Coprocessor 0. Now when the exception handling routine returns, execution resumes at the branch.

If you recall back in Part 5 the exception handling method we added to Coprocessor 0 took a branch parameter

uint32_t COP0::EnterException(uint32_t code, uint32_t epc, uint32_t branch) {

WriteRegisterMasked(SR, 0x0000003Fu, ReadRegister(SR) << 2u);

WriteRegisterMasked(CAUSE, 0x8000007Cu, (branch << 31u) + ((code & 0x1Fu) << 2u));

WriteRegister(EPC, epc);

return BOOT_EXCEPTION_VECTOR;

}

and bit 31 (called the BD field in the MIPS documentation) of the CAUSE register is set accordingly. The BD field is there to tell exception handling routines that the instruction that raised the exception was at EPC + 4 and not at EPC in these cases.

This code also assumes that the caller is passing the correct value of the Exception Program Counter (the epc parameter).

This means, that to begin with at the very least, we’re going to have to modify our EnterException method that we’ve been using to date to take an extra parameter

void EnterException(R3051* r3051, uint32_t code, uint32_t branch) {

const uint32_t epc = ReadPC(r3051);

const uint32_t pc = r3051->Cop0().EnterException(code, epc, branch);

WritePC(r3051, pc);

}

This also unfortunately means that we’re going to have to modify the code around StoreWord and LoadWord. They call EnterException and therefore they’re going to need to be able to pass the correct information as the branch parameter.

The simplest approach would be to write the branch slot information back to the interpreter prior to attempting to interact with memory. This will work, but it’s one more thing we have to remember to do. Alternatively, we could change StoreWord and LoadWord to take a branch parameter or, we could stop relying on StoreWord and LoadWord to do so much work for us and move more of their code into the recompiler.

The example in this section also touches upon another problem with load delay-slots. In the last part we discussed how me might, with the aid of Static single-assignment, potentially eliminate the need for load delay-slots in the recompiler by arranging things so that we never returned control back to the recompiler with the Guest Processor about to execute a load delay-slot instruction.

However, with a load instruction in a branch delay-slot, at the moment our naive recompiler will do this. It might be possible to work around this by having the recompiler always follow the branch instruction if there’s a load instruction in the branch delay-slot, but this is left as an exercise for the reader.

I think we’ve been in here too long. I feel unusual.

There’s one further wrinkle that needs discussing before we can move on to presenting code. What do you think the correct behaviour should be here?

loop_1:

ADDI R5, 1

...

loop_2:

BGTZ R4, loop_1 ; branch

BGTZ R4, loop_2 ; branch in branch delay-slot

Turns out that this is tricky. The R3000 reference manual says that a branch delay slot may not itself be occupied by a jump or branch instruction. The error is not detected and the results of such an operation are undefined.

The behaviour is therefore unpredictable. One may imagine, given the pipelined nature of the R3000, that in the example above the ADDI instruction is moved into the pipeline as a result of the first branch. The ADDI is effectively in the delay-slot of the second BGTZ and when it completes the second branch takes effect and the execution moves back to loop_23.

Without access to hardware to do any sort of extensive testing there’s no way to tell what the actual behaviour is and as the existing documentation explicitly says this behaviour is undefined we will assume for now that we won’t encounter this scenario in practice.

Free to those who can afford it, very expensive to those who can’t.

After that fairly lengthy preamble let’s start by extending our RecompilerState object

class RecompilerState {

private:

...

uint32_t branchTarget;

bool branchDelaySlot;

bool branchDelaySlotNext;

uint32_t pc;

};

The branchTarget holds the address of the instruction at the branch target. The branchDelaySlot and branchDelaySlotNext fields work like their load-delay slot analogues and the pc field holds the address of the instruction we’re currently recompiling.

Our recompiler loop will then take the form

RecompilerState state(200u /* initial PC */);

for (const uint32_t opcode : opcodes) {

Emit(state, emitter, processor, opcode);

state.SetPC(state.GetPC() + 4u);

if (state.GetBranchDelaySlot()) {

break;

}

bool branchDelaySlotNext = state.GetBranchDelaySlotNext();

state.SetBranchDelaySlot(branchDelaySlotNext);

state.SetBranchDelaySlotNext(false);

}

// ??? Branch and epilogue ???

which is similar to the recompiler loop for dealing with delay-slots discussed in Part 7. (The load delay-slot particulars have been removed for clarity, so we can focus on branches).

After emitting every instruction we increment the recompiler’s copy of the Program Counter by four, and then we check to see if the last emitted instruction occupied a branch delay-slot, and if it did then we need to stop recompiling and complete the branch in the function epilogue.

Yet again that oaf has destroyed my day!

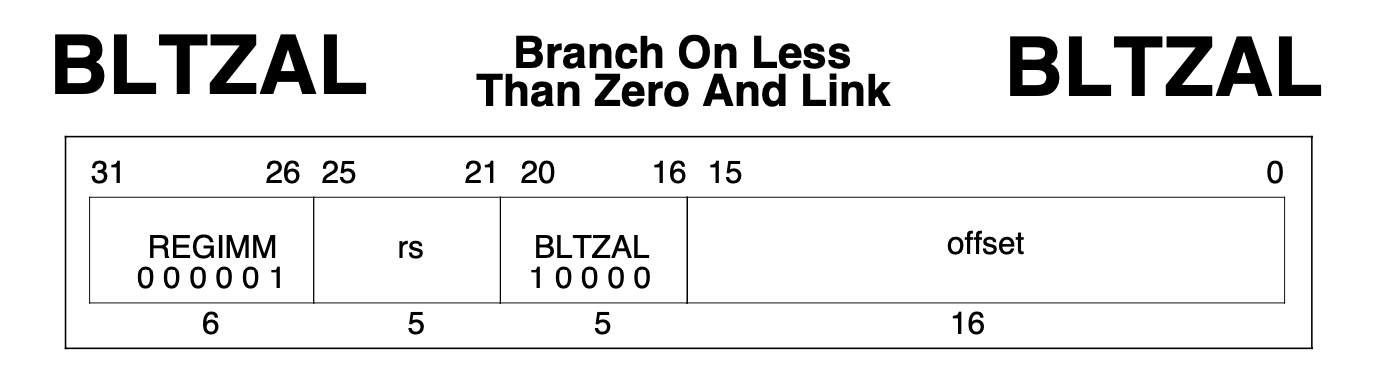

We begin the discussion on how to complete the branch operation by looking at one of the more interesting branch instructions in the MIPS instruction set, BLTZAL.

It’s an I-Type instruction and BLTZAL stands for Branch Less Than Zero And Link.

What this is instruction does is write the value of the Program Counter plus 8 into the Link Register and then compare the contents of register Rs with zero.

What is a Link Register? Link Registers are used in RISC type architectures to store the return address from a jump or a branch. This saves the processor from having to access memory, such as the stack, to store the return address which could be significantly slower. In the MIPS architecture R31 serves as the Link Register.

If Rs was less than zero then the processor will jump to the Program Counter plus the sign-extended offset plus 4.

There is of course one further detail to consider. How do we store the result of the comparison over the duration of the delay-slot? As to why we have to do this, consider the following MIPS code:

BLTZAL R6, target

ADDIU R7, R5, 1 ; work in the delay slot

The recompiled version BLTZAL might use one of the host instructions to compare the contents of R6 with zero and the RFLAGS register will get updated accordingly. So far so good, but the problem comes when the recompiled version of ADDIU performs the necessary addition operations and these operations end up modifying the RFLAGS as well.

In the current scheme it’s also not possible to simply delay the comparison until after the instruction in the delay-slot since this scenario is also possible

BLTZAL R6, target

ADDIU R6, R5, 1 ; update the comparison register in the delay slot

and the register we want to use for the comparison will have been updated.

In order to solve this problem in a way that is broadly compatible with the previous parts, we’re going to store the result of the comparison on the stack. I don’t think this is the ideal solution, far from it, but it should suffice for now.

I’m preparing myself to forgive you.

Let’s reserve 4-bytes at RBP - 8 to hold a 1-bit flag saying that if we should branch (1) or continue (0) at the end of this block. We do this so that unconditional branches don’t have to do any additional work, but this does have the downside that conditional branches have to update the flag to say they don’t want to branch.

We set this up in the recompiled prologue with

constexpr uint8_t BRANCH_DECISION_OFFSET = -8;

EmitterX64 emitter(buffer);

emitter.PushR64(RBP);

emitter.MovR64R64(RBP, RSP);

emitter.SubR64Imm8(RSP, 16);

emitter.MovR32Imm32(RAX, 1u); // Move 1 into the branch decision variable to indicate we want to branch

emitter.MovDisp8R32(RBP, BRANCH_DECISION_OFFSET, RAX);

which sets up the BRANCH_DECISION variable appropriately.

The recompiled epilogue needs to be modified to check this variable and decide if what value the returned Program Counter should be set to

// Load the branch decision into RAX

Label resume = emitter.NewLabel();

Label epilogue = emitter.NewLabel();

emitter.MovR32Disp8(RAX, RBP, BRANCH_DECISION_OFFSET);

// Fix up the processor's Program Counter appropriately

emitter.CmpR32Imm8(RAX, 1u);

emitter.Jne(resume);

CallInterpreterFunction(emitter, AddressOf(WritePC), processor, state.GetBranchTarget());

emitter.Jmp(epilogue);

emitter.Bind(resume);

CallInterpreterFunction(emitter, AddressOf(WritePC), processor, state.GetPC());

emitter.Bind(epilogue);

// Epilogue

...

it does this by loading the BRANCH_DECISION variable into RAX and then comparing it with 1. If they’re not equal (i.e. the value is 0) then we don’t want to branch and so the code will jump to the resume label. Otherwise, we set the Program Counter to the value of the Branch Target and jump unconditionally to the epilogue.

The new functions here in the Emitter are CmpR32Imm8 and Jmp which hopefully shouldn’t offer too much in the way of surprise4

void EmitterX64::CmpR32Imm8(uint32_t rm, uint8_t imm8) {

const uint8_t rex = Rex(0u, 0u, 0u, rm >> 3u);

const uint8_t mod = ModRM(3u, 7u, rm);

buffer.Bytes({rex, 0x83u, mod, imm8});

}

void EmitterX64::Jmp(const Label& label) {

buffer.Bytes({ 0xEBu, 0x00u });

const size_t position = buffer.Position();

if (label.Bound()) {

FixUpCallSite(static_cast<CallSite>(position), label);

} else {

callSites[label.Id()].emplace_back(position);

}

}

I think you’ve been punished enough.

Our implementation of EmitBltzal is then, finally, as follows

void EmitBltzal(

RecompilerState &state, EmitterX64 &emitter,

R3051 &processor, uint32_t opcode) {

// Extract fields from instruction

const uint32_t rs = InstructionRs(opcode);

const uint32_t offset = InstructionImmediateExtended(opcode) << 2u;

const size_t size = sizeof(uint32_t);

// Load the address of the registers into RDX

emitter.MovR64Imm64(RDX, processor.RegisterAddress(0));

// Write the PC plus 8 to R31

emitter.MovR32Imm32(RAX, state.GetPC() + 8u);

emitter.MovDisp8R32(RDX, static_cast<uint8_t>(31u * size), RAX);

// Load RS into RAX

emitter.MovR32Disp8(RAX, RDX, static_cast<uint8_t>(rs * size));

// Compare RAX with zero

emitter.CmpR32Imm8(RAX, 0u);

// If RAX was negative skip clearing the BRANCH_DECISION flag

Label resume = emitter.NewLabel();

emitter.Js(resume);

emitter.MovR32Imm32(RAX, 0u); // EOR RAX, RAX would be better

emitter.MovDisp8R32(RBP, BRANCH_DECISION_OFFSET, RAX);

emitter.Bind(resume);

// Do necessary bookkeeping

state.SetBranchDelaySlotNext(true);

state.SetBranchTarget(state.GetPC() + 4u + offset);

}

The method uses RDX to hold the address of the first register and that’s used to first write the value of Program Counter plus 8 to R31 and then load RS into RAX.

RAX is then compared with zero using the CmpR32Imm8 function developed in the previous section. If the result of this comparison is negative (i.e. Less Than Zero), which in this case since we’re comparing with zero, means that the content of RAX is negative then we want to skip over the code that clears the BRANCH_DECISION variable.

We achieve this with the addition of the Js (Jump Sign) function to the emitter4

void EmitterX64::Js(const Label& label) {

buffer.Bytes({ 0x78u, 0x00u });

const size_t position = buffer.Position();

if (label.Bound()) {

FixUpCallSite(static_cast<CallSite>(position), label);

} else {

callSites[label.Id()].emplace_back(position);

}

}

which jumps if the Sign Flag in the RFLAGS register is set (which indicates the last arithmetic result was negative).

Finally, as in the EmitLW function we do the necessary bookkeeping to tell the main loop that the next instruction is going to be in a branch delay-slot and store the branch target address.

And that, is that! I think we better release you from the legume…

Conclusion

In this part we discussed branches and branch delay-slots in MIPS. We discussed how branches need to be considered when recompiling and we provided a very basic implementation that relied upon the stack to propagate delayed branching information.

This is the end of this series. I hope you found it useful and that it inspired you to investigate the topic further. There’s so much more to be done!

At a minimum:

- Supporting different Calling Conventions

- Register Allocation

- Static Single Assignment

- Intermediate Representation

- Code Analysis and optimisations (removing redundant work, instruction re-ordering, micro-operations)

- Servicing interrupts and other time dependent system events

- Improving the exception handling

- Splitting the cache for exception handling code and normal code

- Exceptions are usually rare and having the handlers interleaved makes the happy path code bigger

- Using a single large code cache rather than having multiple small ones

Before I go I would like to restate that this is not a production grade JIT or recompiler. The goal of the project was to work through the basics and deal with some MIPS architecture peculiarities and improve my own understanding on the topic while hopefully providing a gateway resource for others.

Thank you very much for reading.